(written by my spouse and co-instructor, Michael Moore)

LOVE AND DESIRE ARE BASED ON EXPERIENCING PLEASURE

We use the word love to mean many things. One of these is the feeling of love for our intimate partner. Like all feelings, love can come and go, it waxes and wanes, and yet, there is a logic to these phases of love—the simple logic of pleasure and pain. When our partners are a source of pleasure and delight, we naturally desire to be near them. We enjoy their company and the ease of being close. This spontaneously leads to feelings of love.

Do you recall feeling this way? Maybe yesterday? Last year? A decade ago? How do you treat your beloved when you are feeling love and desire? Typically, with kindness, compassion, and generosity. You have patience and empathy when they are struggling. You can stay connected to your love and appreciation for them—even when you are disappointed or upset about something.

There is an aura of goodwill illuminating everything they do. You see the best in them. You give them the benefit of the doubt. When there is a conflict you take responsibility for your contribution. This is infectious—our partners respond in kind when we treat them these ways, creating a virtuous spiral of goodwill. Nobody has to teach us how to be loving. Love occurs naturally when we trust that our partners are there for us, and will meet our needs, especially our need for bonding.

PHYSICAL AND EMOTIONAL CLOSENESS ARE ESSENTIAL TO WELL-BEING

As children, we are dependent on others to protect us from harm and meet our biological needs. As adults, we can presumably meet our own survival needs—food, shelter, protection. The only critical biological need we cannot meet on our own is our need for bonding—being connected with another person in a way that is both emotionally open and physically close. Without this, people do not thrive.

Infants can die from a lack of bonding, even if their other biological needs are met. Studies from the 1940s suggest that the absence of touch is fatal in about a third of infants, with the remaining showing marked intellectual and emotional deficits. This is one reason why solitary confinement is such a cruel punishment. No one does well without access to bonding. Pets can serve this function to some degree.

Psychological and physical stunting of infants deprived of physical contact, although otherwise fed and cared for… suggests that certain brain chemicals released by touch, or others released in its absence, may account for these infants’ failure to thrive… Contact and touch have a significant role in the infant’s ability to regulate its own responses to stress… For instance, physical contact is the ultimate signal to infants or small children that they are safe… simply being there or reassuring him [or her] is not enough, touch researchers believe.

—Excerpted from “The Experience of Touch: Research Points to a Critical Role” by Daniel Goleman in The New York Times (2/02/88)

While as adults, a lack of bonding may not kill you, it certainly impacts your well-being. It is natural to depend on your intimate partner to meet this core need. However, emotional allergies (more on these later) from past painful experiences may color your expectations of whether or not it is safe to depend on others. While this can be partly based on past experiences with your partner (or previous partners), it is usually early experiences growing up that inform emotional allergies.

PAIN LEADS TO SELF-PROTECTION

Which brings us to the pain side of the equation. When, instead of pleasure, your partner is a source of pain and heartache, you will typically sense danger and instinctively respond with self-protection. Instead of feelings of love, you might feel fear and anger. When emotional allergies are triggered, you may overreact, based on the accumulated hurts from the past. We hand our partners the bill, often unconsciously, for the ways we have been hurt before.

It can be a challenge to stay emotionally connected to your own needs, values and perspectives —as well as those of your partner—when you are faced with a significant disagreement or an apparently irreconcilable difference. Uncomfortable internal tension occurs when your needs appear to be incompatible with the needs of someone you care about and rely upon. This is often further intensified by a number of overlapping stressors.

CHILD-RAISING CHALLENGES

For years, social scientists have known that nonparents are happier than parents. Study after study has confirmed the troubling finding that having kids makes you less happy than your child-free peers. Now new research helps explain the parental happiness gap, suggesting it’s less about the children and more about family support in the country where you live…

The happiness gap between parents and nonparents in the United States is significantly larger than the gap found in other industrialized nations, including Great Britain and Australia. And in other Western countries, the happiness gap is nonexistent or even reversed. Parents in Norway, Sweden and Finland—and Russia and Hungary—report even greater levels of happiness than their childless peers…

The gap could be explained by differences in family-friendly social policies such as subsidized child care and paid vacation and sick leave. In countries that gave parents what researchers called “the tools to combine work and family,” the negative impact of parenting on happiness disappeared.

—Excerpted from “For U.S. Parents, a Troubling Happiness Gap” by KJ Dell’Antonia in The New York Times (6/17/16)

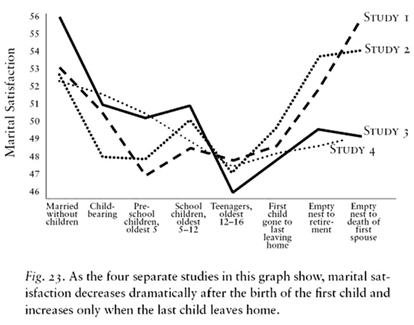

Graph is from Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert

It can also be really difficult when parents do not agree on how to raise their children. For Robin and me, having blended our families, this was by far the most challenging interpersonal issue we faced.

I was raised by my parents to be independent. Both of my parents were orphaned as children. This left them with the sense that it is important to raise children in a way that leads to self-reliance as an adult. In school I was often bored and tended to cut up in order to up the fun level. I was constantly in trouble for this, which did not fit in the very button-downed atmosphere of mid-western schools when I was growing up. I was shocked to discover, as an adult, that my parents agreed with me about how some of that went. They never breathed a word of this to me. They felt it was important for me to find my own way.

Robin is one of the founders of Shining Mountain Waldorf School in Boulder. She is also a family therapist and has worked as a public-school crisis interventionist. Her approach to child-rearing is to emphasize nurture and support for their creative impulses.

Had we been able to blend the best of these perspectives together, we would have, no doubt, been truly amazing parents. Unfortunately, we often became polarized, with me thinking Robin was coddling and her believing that I was being callous. It is sad to reflect on the cost we all paid due to our lack of skillfulness in dealing with these differences.

Whether the issues are privileges, discipline, chores or something else, parenting can become a cauldron of stress for couples if their communication and conflict resolution tools are inadequate.

DEALING WITH OTHER FAMILY MEMBERS

The process of merging two families can be messy. Cultural differences, judgment and jealousy, a lack of agreement about appropriate boundaries—all can add fuel to the challenges you already face as the products of your parent’s marriages.

Taking care of an elderly parent or otherwise disabled family member can create stress due to the emotional and physical strains of caregiving. Being “on call” can leave caregivers less available for work, other family members or friends, or the kinds of self-care that promote resiliency.

WORK AND FINANCIAL PRESSURES

Losing a job or undergoing a challenging work transition can have a huge impact on couples and relationships. You may have to spend long hours at work or time away from home. Tension at your job, especially when you feel you have to suppress your real feelings about things, can easily spill over when you get home. Employment-based loneliness and frustration can become misdirected onto your loved ones.

Modern technologies have vastly improved our lives in so many ways. We live in a place and time of unprecedented affluence. Paradoxically, this has materially added to our stress. We are constantly bombarded by information and distractions clamoring for our attention. Unless well-managed, these constant inputs diminish the quality of attention that remains for our loved ones.

We are also encouraged by advertising and media to indulge ourselves, to assume it is our right to do so, which may lead to financial overwhelm. Even when finances are in good shape, an unexpected medical crisis can change everything.

Of course, there is nothing like a divorce to really break the bank.

EMOTIONAL ALLERGIES

This is by no means a comprehensive list of the stressors that can make it difficult to be at your best with your spouse—resilient and available for the best you can offer each other. However, these issues are vastly more difficult to manage when they lead us to become more vulnerable to something we call emotional allergies.

Ever have a moment where your partner says or does some simple thing that really gets your goat—bothering you all out of proportion to what may have actually happened? In fact, you may not have even accurately perceived what was said or done that triggered you in the first place.

When I have one of these moments and my reaction triggers my partner in a similar way, we can go downhill together in a hurry. We can map this relationship doom spiral in our work together, which has universal qualities, but is also unique to every couple in the specific ways it plays out.

We all have emotional allergies. They are the memories (conscious or buried) of earlier, similar experiences that involved feelings such as fear, anxiety, helplessness and unmet needs.

BIOLOGICAL AND EVOLUTIONARY ORIGINS

In the human body, reflex signals travel at about 250 mph. This is the wiring that automatically assesses and responds to threats. This is far faster than the 70 mph speed of circuits associated with conscious thoughts.

When you are triggered by an emotional allergy (perceived danger based on previous experience), your survival mechanisms instantly react. They prepare you to fight, freeze or flee by increasing heart rate, constricting blood vessels and releasing stress hormones. Your nostrils flare, sweat appears, our hair stands up, your mouth goes dry, your pupils dilate, and your digestion shuts down. Meanwhile, clotting factors enter your blood stream and your body is flooded with extra sugars and oxygen. You might start to pant. You can be in full physical reaction mode before you are even aware of the actual trigger. When it comes to danger, the “need for speed” trumps discrimination.

When something happens with your partner that reminds you of an early experience that was threatening, your biological memory response can lead you to overreact. Having such intense feelings and being in an immediate state of high alert, it can be easy to assume that your partner must have done something terribly wrong.

Fortunately, you also possess circuits to self-sooth and reverse the agitation. Once you become aware of being emotionally triggered or flooded, you can then choose a different path—to act as emotional adults.

Some of us get a taste of these feelings when we mistake a stick for a snake. Once we ascertain that what we are looking at is just a stick, we calm down, but it can take a little bit.

The brain can produce emotional responses in us that have very little to do with what we think we’re dealing with or talking about or thinking about at the time. In other words, emotional reactions can be elicited independent of our conscious thought processes. For example, we’ve found pathways that take information into the amygdala without first going through the neocortex, which is where you need to process it in order to figure out exactly what it is and be conscious of it. So, emotions can be and, in fact, probably are mostly processed at an unconscious level. We become conscious and aware of all this after the fact.

—Joseph LeDoux PhD, author of The Emotional Brain and The Integrated Mind

THE GRIP OF EARLY PATTERNING

In what ways did your needs matter as a child? Was it even okay to express them? These youngest parts of you tend to reappear most acutely with the people you are closest to and rely upon the most. Your entire emotional history around getting your needs met resurfaces when you are in an intimate, committed relationship.

Under stress, in a reactive state, we often respond in a style reminiscent of our adolescence, childhood, or even infancy (when we were dependent on others to provide most of our basic needs). This includes a diminished capacity to feel empathy. We tend to focus our attention on how we can change our partners—whom we feel disconnected from—in an attempt to quickly resolve the sense of threat or lack of control. As a result, it becomes a challenge to care for your partner as they are, a person separate from you, with their own needs and perspectives, while also staying in touch with your own legitimate needs. This takes two forms:

Distancing—You lose your capacity to feel empathy for others and their experience. You conclude that you need to either get away from them or demand that they change in order for you to feel okay.

Fusion—You conclude that your own needs are not important enough to risk alienating your partner. Feeling dependent on them, you focus on doing whatever it takes to placate them, putting your own needs and desires on the back burner.

MAKING IT ALL ABOUT YOU

In both cases, we mobilize to change our partners as we feel increasingly disconnected, worried or dissatisfied. Our attention and energy become focused on who we need them to be or how we need them to feel or react, rather than on how they are actually feeling and reacting. We make them responsible for soothing our distraught state and preserving our equanimity.

How do you treat your partner when you are feeling distrustful and unsafe? Instead of bringing empathy, patience and goodwill, you might react as if they were a threat. We attack and blame or withdraw and hide. The old methods of self-protection we learned as dependent children return when we feel like we have to choose between making our partner happy at our own expense (appeasing or fusion) or protecting ourselves and losing them (distance and aloneness).

Of course, our partners tend to respond in kind when we treat them in these ways, so we can fall into a self-perpetuating spiral of negativity. We become disconnected from one another, cut off from our primary source of emotional openness and physical closeness, and can easily descend into alienation and despair.

THE OPPORTUNITY

Marriage is the central relationship for most adults and has beneficial effects for health. At the same time, troubled marriages have negative health consequences… unhappy marriages are associated with morbidity and mortality… Marital functioning influences health: the cardiovascular, endocrine, and immune systems. Across these studies, negative and hostile behaviors during marital conflict discussions are related to elevations in cardiovascular activity, alterations in hormones related to stress, and dysregulation of immune function.

—Excerpted from “The Physiology of Marriage: Pathways to Health” by Robles and Kiecolt-Glaser in Physiology and Behavior (08/2003)

This challenging situation of a confluence of relational stressors also offers an opportunity to increase your emotional resiliency—both with your partner and also in service of your own growth and development. Unforeseen creative solutions arise as you enhance your capacity for self-soothing, empathy and self-awareness. When you can maintain conscious awareness and emotional connection (empathy) with your own needs and desires—as well as your partner’s—you will access all your resources, rather than the greatly diminished repertoire available in a reactive state.

So, how can you learn from the pain side of things and spend more time on the pleasure side?

First, you have to learn to identify your needs and teach your partner how to fulfill them. We can only meet each other’s needs if we understand them. This involves the skills of listening and confiding, the tools we learn and apply in our work together.

Second, when there is a disruption in the trust and love, and you find ourselves on the pain side of the map, you will need effective tools to rapidly repair the connection and reestablish your bond. Each time you do so, you will build empathy for one another and trust in your relationship.

The truth is that pain is part of life and, sometimes, is essential to your growth and development as fully functional adults. The point is not to avoid the pain we sometimes experience in relationship and seek only pleasure. The point is to identify when you are in pain, learn whatever is being revealed to you, and get back to the pleasure side. In other words, to avoid being stuck you can create value out of all your experiences—the great ones as well as the challenging ones.

The practical, proven tools we offer, when applied, will allow you to consistently accomplish strategies for creating meaningful connection and lasting goodwill. In this way, you can sustain the feeling of authentic love and a relationship based on loving-kindness.

Neural correlates of long-term romantic love were investigated. Results showed activation specific to the partner in dopamine-rich brain regions associated with reward, motivation and ‘wanting’ consistent with results from early-stage romantic love studies. These data suggest that the reward-value associated with a long-term partner may be sustained, similar to new love…

[However] unlike findings for newly in love individuals, those in long term, in love marriages showed activation in brain regions associated with… attachment bonding.

—Excerpted from “Neural Correlates of Long-term Intense Romantic Love” by Acevedo, Aron, Fisher and Brown in Social, Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience (02/12)

Or to quote from one of our graduates in less scientific, but perhaps more compelling, language:

I sometimes feel like a man who has gotten out of a bad marriage and is having a fling with someone else. I keep thinking, Boy am I glad to be done with that relationship. Then I stop and realize that I am glad to have the depth that having stuck with this one gives me, because I have both at the same time.

—Elementary school teacher